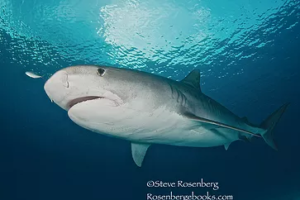

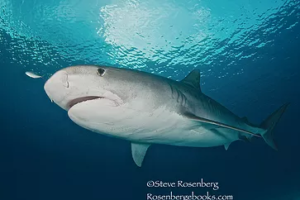

Although tiger sharks, Galeocerdo cuvier, have long been considered dangerous to humans, today there are a growing number of dive operations worldwide that focus on putting divers and the sharks in the water together. While some shark experts assert that these encounters are just an accident waiting to happen, it is interesting to note that despite baiting, close proximity and almost daily interactions over the course of more than 10 years, there have been no reported attacks specifically involving tiger sharks and divers.

Although tiger sharks, Galeocerdo cuvier, have long been considered dangerous to humans, today there are a growing number of dive operations worldwide that focus on putting divers and the sharks in the water together. While some shark experts assert that these encounters are just an accident waiting to happen, it is interesting to note that despite baiting, close proximity and almost daily interactions over the course of more than 10 years, there have been no reported attacks specifically involving tiger sharks and divers.

Partially to thank for that record are reputable dive operations that set up strict guidelines for these interactions, and which require all of their divers to adhere to a strict set of rules. When these big predators show up, divers are required to continuously track them, maintain eye contact and point them out to the rest of the group.

Up-close, personal encounters have taught me that tiger sharks generally swim slowly and deliberately. When there are bait boxes in the water, other sharks, such as lemons and bulls, will swim directly to the bait. The tigers, however, approach warily, with their noses to the sand as if following a scent like a bloodhound. Ordinarily they don’t immediately compete with the other sharks, instead taking their time to investigate the smell. Despite their sluggish behavior, tiger sharks are very strong swimmers and extremely fast when they want to be. Their high back and dorsal fin can be used as a pivot, allowing them to spin quickly on their axis. This is why dive operations insist that divers maintain eye contact and keep track of the sharks as they pass, especially when they are nearby.

Up-close, personal encounters have taught me that tiger sharks generally swim slowly and deliberately. When there are bait boxes in the water, other sharks, such as lemons and bulls, will swim directly to the bait. The tigers, however, approach warily, with their noses to the sand as if following a scent like a bloodhound. Ordinarily they don’t immediately compete with the other sharks, instead taking their time to investigate the smell. Despite their sluggish behavior, tiger sharks are very strong swimmers and extremely fast when they want to be. Their high back and dorsal fin can be used as a pivot, allowing them to spin quickly on their axis. This is why dive operations insist that divers maintain eye contact and keep track of the sharks as they pass, especially when they are nearby.

As soon as the tiger figures out that the smell is coming from the bait box, it often becomes focused and determined. I have seen a shark suddenly swim directly to the crate and grab the whole box, or one of the tether ropes, in its mouth and then swim away with its prize in tow.

As soon as the tiger figures out that the smell is coming from the bait box, it often becomes focused and determined. I have seen a shark suddenly swim directly to the crate and grab the whole box, or one of the tether ropes, in its mouth and then swim away with its prize in tow.

Formidable looking animals, these sharks are named for the dark, vertical stripes Tiger sharks are also recognizable by their wide, blunt nose. They have very large mouths, with rows of 18 to 26 sharp, serrated teeth. Their powerful jaws allow them to crack open the shells of sea turtles and large clams.

The stomach contents of captured tiger sharks have revealed almost anything you can imagine, including stingrays, sea snakes, seals, birds, squids, and even license plates and old tires. Large specimens can grow to 18 feet or more (5 meters) and weigh more than 1,900 pounds (900 kilograms). Tigers live up to 50 years in the wild. They have small pits on the snout, which hold electro-receptors called the ampullae of Lorenzini.

The stomach contents of captured tiger sharks have revealed almost anything you can imagine, including stingrays, sea snakes, seals, birds, squids, and even license plates and old tires. Large specimens can grow to 18 feet or more (5 meters) and weigh more than 1,900 pounds (900 kilograms). Tigers live up to 50 years in the wild. They have small pits on the snout, which hold electro-receptors called the ampullae of Lorenzini.

These enable them to detect electric fields, including the weak electrical impulses generated by potential prey. Tiger sharks also have a sensory organ called a lateral line on their flanks that allows them to detect minute vibrations in the water. These adaptations, their excellent eyesight and acute sense of smell make them fearsome nocturnal hunters, able to follow faint traces of blood in the water to their source, even in murky water. The tiger will circle its prey and study it by prodding it with its snout before doing a taste test. This is somewhat reassuring when it is bumping into my camera port. Tigers are not at all shy about coming in close to inspect your cameras and check you out.

These enable them to detect electric fields, including the weak electrical impulses generated by potential prey. Tiger sharks also have a sensory organ called a lateral line on their flanks that allows them to detect minute vibrations in the water. These adaptations, their excellent eyesight and acute sense of smell make them fearsome nocturnal hunters, able to follow faint traces of blood in the water to their source, even in murky water. The tiger will circle its prey and study it by prodding it with its snout before doing a taste test. This is somewhat reassuring when it is bumping into my camera port. Tigers are not at all shy about coming in close to inspect your cameras and check you out.

Diving with tiger sharks at night is an incredible experience, albeit a daunting one, knowing that tigers had been present on the late afternoon dive. The night dives I have participated in have usually been in relatively shallow water, beginning at dusk to let the dive group form a close line on the bottom. Diving directly under the boat with lights mounted at the surface can add enough ambient light to allow divers to spot the sharks before they just appear in front of you.

These awesome predators are found in tropical and subtropical waters worldwide. Off the Atlantic coast of the United States, tiger sharks are found from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. Off the Pacific coast, tiger sharks are found from Southern California southward. They’re found in the Hawaiian, Solomon, and Marshall Islands. In the western Pacific they are found from Australia and New Zealand, up through Indonesia, Fiji and Micronesia and as far north as Japan.

These awesome predators are found in tropical and subtropical waters worldwide. Off the Atlantic coast of the United States, tiger sharks are found from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. Off the Pacific coast, tiger sharks are found from Southern California southward. They’re found in the Hawaiian, Solomon, and Marshall Islands. In the western Pacific they are found from Australia and New Zealand, up through Indonesia, Fiji and Micronesia and as far north as Japan.

It is thought that tiger sharks bear offspring only every two to three years, usually two at a time. The tiger shark is the only species in its family that is ovoviviparous; its eggs hatch internally and the young are born live when fully developed.

It is thought that tiger sharks bear offspring only every two to three years, usually two at a time. The tiger shark is the only species in its family that is ovoviviparous; its eggs hatch internally and the young are born live when fully developed.

Unfortunately, tiger sharks are considered a Near Threatened species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) due to excessive finning and fishing. They are still killed by man for sport. Tigers are especially vulnerable because they grow slowly and take many years to mature. They are also hunted for their livers, which contain high levels of vitamin A that is processed into vitamin oil. This beautiful animal, often characterized as a man-eater, faces far more danger from men than it poses.

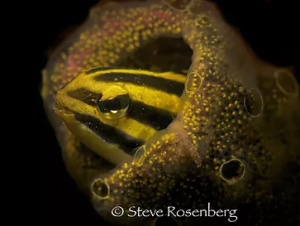

Second, follow the simple rule of getting close, getting down and shooting upward to isolate your subject. Preferably you want to get as close as possible to your subject and fill the frame. Get lower than your subject and shoot upwards to eliminate anything in the frame that may appear behind your subject. If the light from your strobe doesn’t have anything in its path except for the main subject, there is nothing else to reflect the light back to the camera lens. Use a combination of camera control settings, so that there is no visible ambient light. You will be using only artificial light from your strobe(s) to expose the subject.

Second, follow the simple rule of getting close, getting down and shooting upward to isolate your subject. Preferably you want to get as close as possible to your subject and fill the frame. Get lower than your subject and shoot upwards to eliminate anything in the frame that may appear behind your subject. If the light from your strobe doesn’t have anything in its path except for the main subject, there is nothing else to reflect the light back to the camera lens. Use a combination of camera control settings, so that there is no visible ambient light. You will be using only artificial light from your strobe(s) to expose the subject.

The realty is that Cayman’s economy was built in large part upon tourism. One of the main attractions that Grand Cayman provides cruise ship visitors has historically been the warm clear water and the shallow reefs in and around George Town Harbor. Tourists have flocked to Cayman to dive, snorkel and participate in a myriad of water sports and other activities resulting from this natural resource.

The realty is that Cayman’s economy was built in large part upon tourism. One of the main attractions that Grand Cayman provides cruise ship visitors has historically been the warm clear water and the shallow reefs in and around George Town Harbor. Tourists have flocked to Cayman to dive, snorkel and participate in a myriad of water sports and other activities resulting from this natural resource. DEMA, the Dive Equipment and Marketing Association, has also recently weighed in with its opinion that “the construction and operation of this facility will be devastating to the natural coral reefs.” This is based in part on the Environmental Impact Statement commissioned by the Cayman Department of Environment, which found that severe damage would occur due to direct dredging action, turbidity and siltation on the shallow living reefs in and around the Georgetown during construction and additional damage would likely be caused by the on-going dredging required to maintain the berthing facility. It should also be noted that the economic data presented in the Environmental Statement, showed that the Proponent’s argument that ‘the construction of a cruise ship pier would result in an economic benefit to the Cayman Islands” appears to be questionable at best.

DEMA, the Dive Equipment and Marketing Association, has also recently weighed in with its opinion that “the construction and operation of this facility will be devastating to the natural coral reefs.” This is based in part on the Environmental Impact Statement commissioned by the Cayman Department of Environment, which found that severe damage would occur due to direct dredging action, turbidity and siltation on the shallow living reefs in and around the Georgetown during construction and additional damage would likely be caused by the on-going dredging required to maintain the berthing facility. It should also be noted that the economic data presented in the Environmental Statement, showed that the Proponent’s argument that ‘the construction of a cruise ship pier would result in an economic benefit to the Cayman Islands” appears to be questionable at best. It appears that the decision of whether or not to build the cruise ship pier will be a cabinet decision, so all of the legislative assembly members and ministers in the Cayman Government will vote. It should be noted that the daily administration of the islands is conducted by this Cabinet.

It appears that the decision of whether or not to build the cruise ship pier will be a cabinet decision, so all of the legislative assembly members and ministers in the Cayman Government will vote. It should be noted that the daily administration of the islands is conducted by this Cabinet. (Caymanian status holders or Caymanians defined as Cayman born w/ Caymanian parents or grandparents) in the Cayman Islands. It would be a difficult task to assemble that amount of support, but such vote would only require a simple majority to reject the proposal. Sources close to the group have indicated that this effort may very well delay the outcome of this issue or perhaps force a compromise solution to be put in play.

(Caymanian status holders or Caymanians defined as Cayman born w/ Caymanian parents or grandparents) in the Cayman Islands. It would be a difficult task to assemble that amount of support, but such vote would only require a simple majority to reject the proposal. Sources close to the group have indicated that this effort may very well delay the outcome of this issue or perhaps force a compromise solution to be put in play. here are a number of very interesting fishes in the Caribbean. One of my favorites is certainly the Smooth Trunkfish, Rhimesomus triqueter, a member of the family of fishes called boxfish. These slow-moving reef fish can be one of the most entertaining fish to watch on a dive. They are easily recognizable by their shape, coloration and their unique means of propulsion.

here are a number of very interesting fishes in the Caribbean. One of my favorites is certainly the Smooth Trunkfish, Rhimesomus triqueter, a member of the family of fishes called boxfish. These slow-moving reef fish can be one of the most entertaining fish to watch on a dive. They are easily recognizable by their shape, coloration and their unique means of propulsion.

The general background color is dark shades of black to brown, with a pattern of small white spots. If you look closely, you will see that it has hexagonal patterns giving a honeycomb-like appearance in the middle area of the body. The Smooth Trunkfish may have gotten its name because it is the only member of the boxfish family that has no spines above its eyes or by the anal fin.

The general background color is dark shades of black to brown, with a pattern of small white spots. If you look closely, you will see that it has hexagonal patterns giving a honeycomb-like appearance in the middle area of the body. The Smooth Trunkfish may have gotten its name because it is the only member of the boxfish family that has no spines above its eyes or by the anal fin.

Its normal adult size is about 7 to 8 inches in length, although it can get much larger. The smooth trunkfish is normally solitary but sometimes moves around in small groups. In fact, the male trunkfish is thought to have a harem of females in its large territory. I was recently lucky enough to observe some very interesting mating displays within such a group, including dramatic color changes. The scientific names Lactophrys triqueter and Rhimesomus triqueter are synonymous.

Its normal adult size is about 7 to 8 inches in length, although it can get much larger. The smooth trunkfish is normally solitary but sometimes moves around in small groups. In fact, the male trunkfish is thought to have a harem of females in its large territory. I was recently lucky enough to observe some very interesting mating displays within such a group, including dramatic color changes. The scientific names Lactophrys triqueter and Rhimesomus triqueter are synonymous. Although tiger sharks, Galeocerdo cuvier, have long been considered dangerous to humans, today there are a growing number of dive operations worldwide that focus on putting divers and the sharks in the water together. While some shark experts assert that these encounters are just an accident waiting to happen, it is interesting to note that despite baiting, close proximity and almost daily interactions over the course of more than 10 years, there have been no reported attacks specifically involving tiger sharks and divers.

Although tiger sharks, Galeocerdo cuvier, have long been considered dangerous to humans, today there are a growing number of dive operations worldwide that focus on putting divers and the sharks in the water together. While some shark experts assert that these encounters are just an accident waiting to happen, it is interesting to note that despite baiting, close proximity and almost daily interactions over the course of more than 10 years, there have been no reported attacks specifically involving tiger sharks and divers. Up-close, personal encounters have taught me that tiger sharks generally swim slowly and deliberately. When there are bait boxes in the water, other sharks, such as lemons and bulls, will swim directly to the bait. The tigers, however, approach warily, with their noses to the sand as if following a scent like a bloodhound. Ordinarily they don’t immediately compete with the other sharks, instead taking their time to investigate the smell. Despite their sluggish behavior, tiger sharks are very strong swimmers and extremely fast when they want to be. Their high back and dorsal fin can be used as a pivot, allowing them to spin quickly on their axis. This is why dive operations insist that divers maintain eye contact and keep track of the sharks as they pass, especially when they are nearby.

Up-close, personal encounters have taught me that tiger sharks generally swim slowly and deliberately. When there are bait boxes in the water, other sharks, such as lemons and bulls, will swim directly to the bait. The tigers, however, approach warily, with their noses to the sand as if following a scent like a bloodhound. Ordinarily they don’t immediately compete with the other sharks, instead taking their time to investigate the smell. Despite their sluggish behavior, tiger sharks are very strong swimmers and extremely fast when they want to be. Their high back and dorsal fin can be used as a pivot, allowing them to spin quickly on their axis. This is why dive operations insist that divers maintain eye contact and keep track of the sharks as they pass, especially when they are nearby. As soon as the tiger figures out that the smell is coming from the bait box, it often becomes focused and determined. I have seen a shark suddenly swim directly to the crate and grab the whole box, or one of the tether ropes, in its mouth and then swim away with its prize in tow.

As soon as the tiger figures out that the smell is coming from the bait box, it often becomes focused and determined. I have seen a shark suddenly swim directly to the crate and grab the whole box, or one of the tether ropes, in its mouth and then swim away with its prize in tow. The stomach contents of captured tiger sharks have revealed almost anything you can imagine, including stingrays, sea snakes, seals, birds, squids, and even license plates and old tires. Large specimens can grow to 18 feet or more (5 meters) and weigh more than 1,900 pounds (900 kilograms). Tigers live up to 50 years in the wild. They have small pits on the snout, which hold electro-receptors called the ampullae of Lorenzini.

The stomach contents of captured tiger sharks have revealed almost anything you can imagine, including stingrays, sea snakes, seals, birds, squids, and even license plates and old tires. Large specimens can grow to 18 feet or more (5 meters) and weigh more than 1,900 pounds (900 kilograms). Tigers live up to 50 years in the wild. They have small pits on the snout, which hold electro-receptors called the ampullae of Lorenzini. These enable them to detect electric fields, including the weak electrical impulses generated by potential prey. Tiger sharks also have a sensory organ called a lateral line on their flanks that allows them to detect minute vibrations in the water. These adaptations, their excellent eyesight and acute sense of smell make them fearsome nocturnal hunters, able to follow faint traces of blood in the water to their source, even in murky water. The tiger will circle its prey and study it by prodding it with its snout before doing a taste test. This is somewhat reassuring when it is bumping into my camera port. Tigers are not at all shy about coming in close to inspect your cameras and check you out.

These enable them to detect electric fields, including the weak electrical impulses generated by potential prey. Tiger sharks also have a sensory organ called a lateral line on their flanks that allows them to detect minute vibrations in the water. These adaptations, their excellent eyesight and acute sense of smell make them fearsome nocturnal hunters, able to follow faint traces of blood in the water to their source, even in murky water. The tiger will circle its prey and study it by prodding it with its snout before doing a taste test. This is somewhat reassuring when it is bumping into my camera port. Tigers are not at all shy about coming in close to inspect your cameras and check you out. These awesome predators are found in tropical and subtropical waters worldwide. Off the Atlantic coast of the United States, tiger sharks are found from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. Off the Pacific coast, tiger sharks are found from Southern California southward. They’re found in the Hawaiian, Solomon, and Marshall Islands. In the western Pacific they are found from Australia and New Zealand, up through Indonesia, Fiji and Micronesia and as far north as Japan.

These awesome predators are found in tropical and subtropical waters worldwide. Off the Atlantic coast of the United States, tiger sharks are found from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. Off the Pacific coast, tiger sharks are found from Southern California southward. They’re found in the Hawaiian, Solomon, and Marshall Islands. In the western Pacific they are found from Australia and New Zealand, up through Indonesia, Fiji and Micronesia and as far north as Japan. It is thought that tiger sharks bear offspring only every two to three years, usually two at a time. The tiger shark is the only species in its family that is ovoviviparous; its eggs hatch internally and the young are born live when fully developed.

It is thought that tiger sharks bear offspring only every two to three years, usually two at a time. The tiger shark is the only species in its family that is ovoviviparous; its eggs hatch internally and the young are born live when fully developed. They can be constructed very easily from a number of items that you can find at the hardware store or local grocery. My favorite snoot is simply a plastic funnel glued to a diffuser that is made for my Sea & Sea Strobes. A friend aptly nicknamed my creation the “Ghetto Snoot” based on its very intricate design.

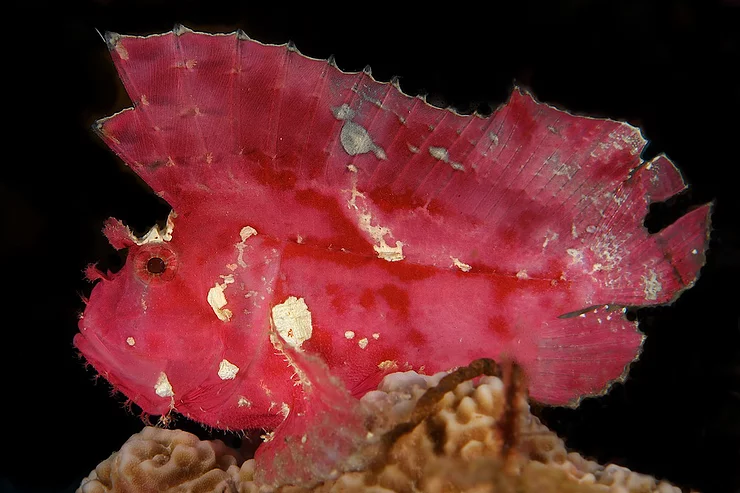

They can be constructed very easily from a number of items that you can find at the hardware store or local grocery. My favorite snoot is simply a plastic funnel glued to a diffuser that is made for my Sea & Sea Strobes. A friend aptly nicknamed my creation the “Ghetto Snoot” based on its very intricate design.

Whether they are used for creating black backgrounds, spotlighting, or for directional lighting, there’s no doubt that snoots can be very helpful tools for creatively lighting underwater subjects. However, as useful as they are, they can be (and often are) very difficult to use. The process of aiming a snoot for macro photography can be very difficult at best. The use of snoots requires patience, practice and luck. However, if you are willing to spend the time and follow a few helpful tips, using snoots can be fun and very helpful in in creating dramatic results to your library of images.

Whether they are used for creating black backgrounds, spotlighting, or for directional lighting, there’s no doubt that snoots can be very helpful tools for creatively lighting underwater subjects. However, as useful as they are, they can be (and often are) very difficult to use. The process of aiming a snoot for macro photography can be very difficult at best. The use of snoots requires patience, practice and luck. However, if you are willing to spend the time and follow a few helpful tips, using snoots can be fun and very helpful in in creating dramatic results to your library of images. Lets face it; the hardest part of using a snoot is pointing that narrow beam of light where you want it to go. The easiest way to do this is by using a strobe that has a built in focusing or modeling light. You simply turn on the light and position the strobe so that the beam hits your subject where you want it to, also paying attention to the direction of the light source. If you don’t have a modeling light, this may become a very frustrating process. Obviously it is easier to use a snoot with a very slow moving or stationary subject. Frogfish, small scorpionfish and virtually any type of weighted plastic marine life will work very well. If your subject is going to stay in the same place you can mount your strobe on a tripod and take the picture. If the angle or placement of the light is a bit off, you can reposition the strobe and take another image. Then you can work on exposure by manually correcting the amount of light by changing the shutter speed, ISO or aperture settings or positioning the strobe a bit closer to your subject. If you are using a small aperture, the light from the strobe will stop action, so you can use a slower shutter speed to change your exposure. If you are using manual settings to control your exposures, remember that you can add or detract light by changing any of these controls, but opening up your aperture will decrease your depth of field. You will usually find that a higher strobe output will work better and give you a more defined spotlight effect.

Lets face it; the hardest part of using a snoot is pointing that narrow beam of light where you want it to go. The easiest way to do this is by using a strobe that has a built in focusing or modeling light. You simply turn on the light and position the strobe so that the beam hits your subject where you want it to, also paying attention to the direction of the light source. If you don’t have a modeling light, this may become a very frustrating process. Obviously it is easier to use a snoot with a very slow moving or stationary subject. Frogfish, small scorpionfish and virtually any type of weighted plastic marine life will work very well. If your subject is going to stay in the same place you can mount your strobe on a tripod and take the picture. If the angle or placement of the light is a bit off, you can reposition the strobe and take another image. Then you can work on exposure by manually correcting the amount of light by changing the shutter speed, ISO or aperture settings or positioning the strobe a bit closer to your subject. If you are using a small aperture, the light from the strobe will stop action, so you can use a slower shutter speed to change your exposure. If you are using manual settings to control your exposures, remember that you can add or detract light by changing any of these controls, but opening up your aperture will decrease your depth of field. You will usually find that a higher strobe output will work better and give you a more defined spotlight effect. Some photographers like to hand hold the “snooted” strobe. I find that this is an option if you have the patience. It certainly allows much more flexibility to change the angle of the light. However, because every minor change in the strobe position will also change your ability to keep the beam of light on your subject, this can be extremely frustrating. My preference is to either use a tripod or, even better, a snoot Sherpa. I should plug a few of my very good friends (James Bassett, Dave Reid and Greg Bassett) who have patiently put up with my excessive snootiness over the years. I have found that if you are going to shoot a moving subject, that this is a necessity unless you are extremely lucky.

Some photographers like to hand hold the “snooted” strobe. I find that this is an option if you have the patience. It certainly allows much more flexibility to change the angle of the light. However, because every minor change in the strobe position will also change your ability to keep the beam of light on your subject, this can be extremely frustrating. My preference is to either use a tripod or, even better, a snoot Sherpa. I should plug a few of my very good friends (James Bassett, Dave Reid and Greg Bassett) who have patiently put up with my excessive snootiness over the years. I have found that if you are going to shoot a moving subject, that this is a necessity unless you are extremely lucky.

Octopuses will often use discarded objects for shelter. Empty containers, such as bottles, cans and clamshells afford excellent refuge for small octopuses. I’ve found they exhibit a remarkable sense of curiosity, even about intruders many times their size. Move slowly and patiently on your dive, and you will often discover they are as curious about us as we are about them.

Octopuses will often use discarded objects for shelter. Empty containers, such as bottles, cans and clamshells afford excellent refuge for small octopuses. I’ve found they exhibit a remarkable sense of curiosity, even about intruders many times their size. Move slowly and patiently on your dive, and you will often discover they are as curious about us as we are about them. Marine biologists coined the name “coconut octopus” after observing the animals excavating coconut half shells from the ocean floor and carrying them for use as portable shelters — the first documented example of invertebrates using tools and carrying objects for future use. Although octopuses often use foreign objects as shelter, the sophisticated planning ahead of coconut octopuses, in selecting materials, carrying and then reassembling them, is considered far more complex. In recent studies, researchers have observed the animals carrying those half-shells up to 65 feet across the seafloor, where they reassembled them into a roughly spherical hiding place. Interestingly, while the octopuses are transporting the shells, they receive no protection from them, which is highly unusual behavior. It’s even more difficult to keep from laughing out loud and flooding your mask as you watch an octopus tiptoe awkwardly across the sand carrying its shells, and then reassemble them to create a protective shelter.

Marine biologists coined the name “coconut octopus” after observing the animals excavating coconut half shells from the ocean floor and carrying them for use as portable shelters — the first documented example of invertebrates using tools and carrying objects for future use. Although octopuses often use foreign objects as shelter, the sophisticated planning ahead of coconut octopuses, in selecting materials, carrying and then reassembling them, is considered far more complex. In recent studies, researchers have observed the animals carrying those half-shells up to 65 feet across the seafloor, where they reassembled them into a roughly spherical hiding place. Interestingly, while the octopuses are transporting the shells, they receive no protection from them, which is highly unusual behavior. It’s even more difficult to keep from laughing out loud and flooding your mask as you watch an octopus tiptoe awkwardly across the sand carrying its shells, and then reassemble them to create a protective shelter.