Notice Regarding the 2019 Temporary Partial Closure of the Cozumel Marine Park

(As of December 15, 2019, the closure was revoked, but may be reinstated by the Cozumel Marine Park)

There was a partial closure of the Southern Reefs at the island of Cozumel that became effective on October 7, 2019. To clarify the situation, a group led by the Cozumel National Marine Park and several environmental groups, initiated a two-month closure of the reefs from The Palancar Pier south from October 7th to December 15th, 2019, to give these reefs a bit of a rest. Many of the hard corals around the island were infected by diseases called Stony Coral Tissue Loss, SCTL, and White Band Disease, which were first observed in the Miami area back in 2014. The scientists who have been studying these diseases believe that their source is untreated effluent (or liquid waste) from Resorts and/or Cruise Lines. One of the main reasons for the closure was to bring attention to the seriousness of the problem.

In a joint action taken by the Secretary of Environment and Natural Resources, the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (CONANP), and The Advisory Counsel of the Reefs of Cozumel National Park, it was decided that there would be a temporary closure of the Southern part of the Cozumel Marine Park from the Palancar pier south. It was determined that this closure would take effect on October 7, 2019 and continue through December 15, 2019. The stated reason for the temporary suspension of diving and snorkeling activities in this area was to give the reefs some time to recover.

The background story is that by the end of 2018, Cozumel’s coral reefs had seen a huge decline. Hard corals were infected by diseases called Stony Coral Tissue Loss, SCTL, and White Band Disease. White Band Disease gets its name from the white bands of dead coral tissue that it forms. Neither of these should be confused with coral bleaching, which is something entirely different. The suspected bacterial infections spread rapidly killing many species of hard corals. ‘Healthy Reefs,’ a group that tracks the health of the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System, stated that the effect of the disease was “unprecedented” as mortality rates were very high and around 30 different types of hard corals were deemed to be susceptible to it, including brain corals, pillar corals, flower corals and star corals, to name a few.

Among the particularly troubling aspects of this disease outbreak was that the diseases had affected more than one half of reef-building hard coral species. It had also spread quickly and had a high mortality rate among affected hard corals. The scientific community seemed to believe that the disease is transmitted primarily through the water column, but speculated that it could also be transmitted by contact. (*Information provided by the Florida Disease Advisory Committee and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.)

The first sighting of the destruction of these types of corals was in the Miami area in 2014. In Mexico, it was first seen at Puerto Morelos, 45 kilometers south of Cancún, and it made its way to the reefs off Cozumel in early 2018. By late 2018 and early 2019, the disease had spread throughout Pompano Beach, Palm Beach, the Upper Florida Keys, and to parts of the Caribbean including, Jamaica, Saint Maarten, the US Virgin Islands, the Mexican Caribbean, the Dominican Republic, Saint Thomas and Honduras.

The exact cause and source of the disease is still unknown, but scientists believe that it is linked to pollution and possibly the presence of seaweed such as sargassum in seawater. The phenomenon occurs as a result of pollutants (and possibly rising water temperatures), which cause the coral polyps to expel the algae on which they feed, and that live in their tissues. The tissues then disconnect from the coral skeleton, the animals die and the reef loses its color. Researchers are still without solutions to the problem, although the state is working on a massive project, replenishing damaged reefs with laboratory-grown coral. In a couple of areas in the Western Caribbean, (namely along the coastline of the Mexican mainland and in Honduras) there is an effort underway, to replant hundreds of thousands of ‘lab-grown’ corals on the reef. The goal of the project, which began in 2017, is to re-establish healthy corals, hoping that water treatment efforts will minimize the presence of pollution, the probable source of the bacterium.

The Cozumel Marine Park had acknowledged that cruise ships and the mismanagement of waste at coastal hotels in and around the marine park were amongst the most likely causes for the spread of the disease. Although the causal agent of the bacteria is still not clear, most scientists think that the bacteria had evolved from pollution (untreated effluent) dumped in the ocean by Cruise Ships and Resorts. The action taken to close Cozumel’s southern reefs to divers for a two-month period of time in 2019 had done so for two reasons. First, the Park wanted to slow one potential cause of the spread of the bacteria, which was physical touching of the coral by divers. It was reported that Studies had shown that during an average 4-hour period on any given day of the week, there were as many as 2,000 touches by divers in the southern reef area. Second, and perhaps the more important reason, was that the closure would create an awareness of the problems that the reefs in Cozumel were and are facing.

Author’s observations: Many people want to know why the partial closure was ordered and why the partial closure was only for the Southern Reefs (Palancar, Columbia, Chun Chacaab, Maracaibo, Punta Sur, and Cielo). I had spent quite a bit of time in 2019 diving in Cozumel, as well as other nearby destinations such as the Bay Islands on Honduras. In 2019, I observed a lot of SCTLD or “White Band” disease in many areas of Cozumel and the Bay Islands of Honduras. The areas of Cozumel that were affected by the disease ere certainly not limited to the Southern Reefs.

There are new regulations require that the Hotels and Beach Clubs must install water treatment equipment. This is certainly a good thing. It also reported at this time that regulations require Cruise Ship lines to treat their effluent (Liquid waste) before dumping it in the ocean. This is extremely important because this is the most likely source of the bacterium that had attacked the corals. Obviously, sewage treatment is very expensive, but this step is an integral part of the long-term solution.

Based on a study that was undertaken at the request of the Mexican authorities by the German Agency for International Cooperation, there were findings that 1) the Marine Park gets 1.8 million foreign visitors per year and 2) that the average visitor would be happy to pay Three Thousand and Fifty-Two Pesos (US$155.00) per person for use of the Marine Park. There is some indication that the Park is considering the imposition of new use fees on tourists. Most of these visitors to the Marine Park would include tourists who come to Cozumel off of the Cruise Ships for just a few hours and a lesser number of tourists who come to Cozumel specifically to dive. I would speculate that, in reality, a very small percentage of the cruise ship tourists, if any, who were told that they would have to pay $155 to dive or snorkel for a few hours during their one day stay on the island would actually choose to use the Park at such a cost.

A more difficult question would be how potential dive tourists would react to a substantial increase of the use fees they are already paying to use the Marine Park. Cozumel is a wonderful dive destination that offers incredible encounters with beautiful and unique marine Life. However, one of the considerations for many of the divers who come to Cozumel have chosen Cozumel rather than other destinations because it is less expensive.

The Dive Sites that had been subject to the 2019 partial closure.

The dive sites that were closed in Cozumel were all dive sites from the Palancar Pier, South including:

- All of the Palancar dive sites

- Colombia

- Punta Sur

- El Cielo

Final Thoughts

Multiple meetings have been announced to examine the details of the 2019 closure and the effect that the closure has had on tour operators that are concerned about the backlash and economic impacts that the closure had and the future of the State of Cozumel’s coral reefs. There have been discussions that indicate that if the closures are re-instated in the future, there may be a rotation of the closures throughout various areas of the Marine Park.

Many marine-park business permit holders have asked to have a PROFEPA office in Cozumel that can police the marine park and keep out the many illegal dive and snorkel operators as well as illegal fishing that occurs daily within the marine park. PROFEPA is the institution in charge of formulating and conducting the inspection and surveillance policy on the conservation and protection of aquatic species at risk and of protected natural areas that include coastal and marine ecosystems.

Finally, Cozumel has much to offer for visiting divers. It is an excellent destination that offers much to see and experience. There are countless groups that are working hard to address the many issues that the world’s oceans face from population pressures. I, for one, am confident that Cozumel will remain one of the top destinations in the Caribbean for visiting tourists and I will not hesitate to bring groups of divers to Cozumel to experience the beauty and excitement of this great dive destination.

here are a number of very interesting fishes in the Caribbean. One of my favorites is certainly the Smooth Trunkfish, Rhimesomus triqueter, a member of the family of fishes called boxfish. These slow-moving reef fish can be one of the most entertaining fish to watch on a dive. They are easily recognizable by their shape, coloration and their unique means of propulsion.

here are a number of very interesting fishes in the Caribbean. One of my favorites is certainly the Smooth Trunkfish, Rhimesomus triqueter, a member of the family of fishes called boxfish. These slow-moving reef fish can be one of the most entertaining fish to watch on a dive. They are easily recognizable by their shape, coloration and their unique means of propulsion.

The general background color is dark shades of black to brown, with a pattern of small white spots. If you look closely, you will see that it has hexagonal patterns giving a honeycomb-like appearance in the middle area of the body. The Smooth Trunkfish may have gotten its name because it is the only member of the boxfish family that has no spines above its eyes or by the anal fin.

The general background color is dark shades of black to brown, with a pattern of small white spots. If you look closely, you will see that it has hexagonal patterns giving a honeycomb-like appearance in the middle area of the body. The Smooth Trunkfish may have gotten its name because it is the only member of the boxfish family that has no spines above its eyes or by the anal fin.

Its normal adult size is about 7 to 8 inches in length, although it can get much larger. The smooth trunkfish is normally solitary but sometimes moves around in small groups. In fact, the male trunkfish is thought to have a harem of females in its large territory. I was recently lucky enough to observe some very interesting mating displays within such a group, including dramatic color changes. The scientific names Lactophrys triqueter and Rhimesomus triqueter are synonymous.

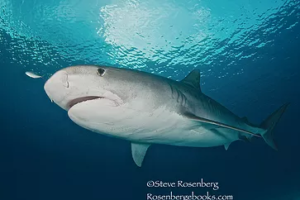

Its normal adult size is about 7 to 8 inches in length, although it can get much larger. The smooth trunkfish is normally solitary but sometimes moves around in small groups. In fact, the male trunkfish is thought to have a harem of females in its large territory. I was recently lucky enough to observe some very interesting mating displays within such a group, including dramatic color changes. The scientific names Lactophrys triqueter and Rhimesomus triqueter are synonymous. Although tiger sharks, Galeocerdo cuvier, have long been considered dangerous to humans, today there are a growing number of dive operations worldwide that focus on putting divers and the sharks in the water together. While some shark experts assert that these encounters are just an accident waiting to happen, it is interesting to note that despite baiting, close proximity and almost daily interactions over the course of more than 10 years, there have been no reported attacks specifically involving tiger sharks and divers.

Although tiger sharks, Galeocerdo cuvier, have long been considered dangerous to humans, today there are a growing number of dive operations worldwide that focus on putting divers and the sharks in the water together. While some shark experts assert that these encounters are just an accident waiting to happen, it is interesting to note that despite baiting, close proximity and almost daily interactions over the course of more than 10 years, there have been no reported attacks specifically involving tiger sharks and divers. Up-close, personal encounters have taught me that tiger sharks generally swim slowly and deliberately. When there are bait boxes in the water, other sharks, such as lemons and bulls, will swim directly to the bait. The tigers, however, approach warily, with their noses to the sand as if following a scent like a bloodhound. Ordinarily they don’t immediately compete with the other sharks, instead taking their time to investigate the smell. Despite their sluggish behavior, tiger sharks are very strong swimmers and extremely fast when they want to be. Their high back and dorsal fin can be used as a pivot, allowing them to spin quickly on their axis. This is why dive operations insist that divers maintain eye contact and keep track of the sharks as they pass, especially when they are nearby.

Up-close, personal encounters have taught me that tiger sharks generally swim slowly and deliberately. When there are bait boxes in the water, other sharks, such as lemons and bulls, will swim directly to the bait. The tigers, however, approach warily, with their noses to the sand as if following a scent like a bloodhound. Ordinarily they don’t immediately compete with the other sharks, instead taking their time to investigate the smell. Despite their sluggish behavior, tiger sharks are very strong swimmers and extremely fast when they want to be. Their high back and dorsal fin can be used as a pivot, allowing them to spin quickly on their axis. This is why dive operations insist that divers maintain eye contact and keep track of the sharks as they pass, especially when they are nearby. As soon as the tiger figures out that the smell is coming from the bait box, it often becomes focused and determined. I have seen a shark suddenly swim directly to the crate and grab the whole box, or one of the tether ropes, in its mouth and then swim away with its prize in tow.

As soon as the tiger figures out that the smell is coming from the bait box, it often becomes focused and determined. I have seen a shark suddenly swim directly to the crate and grab the whole box, or one of the tether ropes, in its mouth and then swim away with its prize in tow. The stomach contents of captured tiger sharks have revealed almost anything you can imagine, including stingrays, sea snakes, seals, birds, squids, and even license plates and old tires. Large specimens can grow to 18 feet or more (5 meters) and weigh more than 1,900 pounds (900 kilograms). Tigers live up to 50 years in the wild. They have small pits on the snout, which hold electro-receptors called the ampullae of Lorenzini.

The stomach contents of captured tiger sharks have revealed almost anything you can imagine, including stingrays, sea snakes, seals, birds, squids, and even license plates and old tires. Large specimens can grow to 18 feet or more (5 meters) and weigh more than 1,900 pounds (900 kilograms). Tigers live up to 50 years in the wild. They have small pits on the snout, which hold electro-receptors called the ampullae of Lorenzini. These enable them to detect electric fields, including the weak electrical impulses generated by potential prey. Tiger sharks also have a sensory organ called a lateral line on their flanks that allows them to detect minute vibrations in the water. These adaptations, their excellent eyesight and acute sense of smell make them fearsome nocturnal hunters, able to follow faint traces of blood in the water to their source, even in murky water. The tiger will circle its prey and study it by prodding it with its snout before doing a taste test. This is somewhat reassuring when it is bumping into my camera port. Tigers are not at all shy about coming in close to inspect your cameras and check you out.

These enable them to detect electric fields, including the weak electrical impulses generated by potential prey. Tiger sharks also have a sensory organ called a lateral line on their flanks that allows them to detect minute vibrations in the water. These adaptations, their excellent eyesight and acute sense of smell make them fearsome nocturnal hunters, able to follow faint traces of blood in the water to their source, even in murky water. The tiger will circle its prey and study it by prodding it with its snout before doing a taste test. This is somewhat reassuring when it is bumping into my camera port. Tigers are not at all shy about coming in close to inspect your cameras and check you out. These awesome predators are found in tropical and subtropical waters worldwide. Off the Atlantic coast of the United States, tiger sharks are found from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. Off the Pacific coast, tiger sharks are found from Southern California southward. They’re found in the Hawaiian, Solomon, and Marshall Islands. In the western Pacific they are found from Australia and New Zealand, up through Indonesia, Fiji and Micronesia and as far north as Japan.

These awesome predators are found in tropical and subtropical waters worldwide. Off the Atlantic coast of the United States, tiger sharks are found from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea. Off the Pacific coast, tiger sharks are found from Southern California southward. They’re found in the Hawaiian, Solomon, and Marshall Islands. In the western Pacific they are found from Australia and New Zealand, up through Indonesia, Fiji and Micronesia and as far north as Japan. It is thought that tiger sharks bear offspring only every two to three years, usually two at a time. The tiger shark is the only species in its family that is ovoviviparous; its eggs hatch internally and the young are born live when fully developed.

It is thought that tiger sharks bear offspring only every two to three years, usually two at a time. The tiger shark is the only species in its family that is ovoviviparous; its eggs hatch internally and the young are born live when fully developed. Octopuses will often use discarded objects for shelter. Empty containers, such as bottles, cans and clamshells afford excellent refuge for small octopuses. I’ve found they exhibit a remarkable sense of curiosity, even about intruders many times their size. Move slowly and patiently on your dive, and you will often discover they are as curious about us as we are about them.

Octopuses will often use discarded objects for shelter. Empty containers, such as bottles, cans and clamshells afford excellent refuge for small octopuses. I’ve found they exhibit a remarkable sense of curiosity, even about intruders many times their size. Move slowly and patiently on your dive, and you will often discover they are as curious about us as we are about them. Marine biologists coined the name “coconut octopus” after observing the animals excavating coconut half shells from the ocean floor and carrying them for use as portable shelters — the first documented example of invertebrates using tools and carrying objects for future use. Although octopuses often use foreign objects as shelter, the sophisticated planning ahead of coconut octopuses, in selecting materials, carrying and then reassembling them, is considered far more complex. In recent studies, researchers have observed the animals carrying those half-shells up to 65 feet across the seafloor, where they reassembled them into a roughly spherical hiding place. Interestingly, while the octopuses are transporting the shells, they receive no protection from them, which is highly unusual behavior. It’s even more difficult to keep from laughing out loud and flooding your mask as you watch an octopus tiptoe awkwardly across the sand carrying its shells, and then reassemble them to create a protective shelter.

Marine biologists coined the name “coconut octopus” after observing the animals excavating coconut half shells from the ocean floor and carrying them for use as portable shelters — the first documented example of invertebrates using tools and carrying objects for future use. Although octopuses often use foreign objects as shelter, the sophisticated planning ahead of coconut octopuses, in selecting materials, carrying and then reassembling them, is considered far more complex. In recent studies, researchers have observed the animals carrying those half-shells up to 65 feet across the seafloor, where they reassembled them into a roughly spherical hiding place. Interestingly, while the octopuses are transporting the shells, they receive no protection from them, which is highly unusual behavior. It’s even more difficult to keep from laughing out loud and flooding your mask as you watch an octopus tiptoe awkwardly across the sand carrying its shells, and then reassemble them to create a protective shelter.